By Deena Dlusy-Apel

Throughout the ages religious, social and political issues have been addressed by artists. Most of these issues were of a public nature, but also of personal concern to the artist. It is now common for people to discuss personal issues to alleviate the tensions that surround the unspoken. What better way to do this than through art.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1989. One week after surgery, in an art class,Topsy Turvy appeared—a self-portrait with breasts all over the canvas.

Although I had come from a home with a very political father and had a comprehensive understanding of where I stood on most matters, it took a mentor like Sharon Batt, one of the founders of BCAM, to get me to question the existing practices of our medical system and structure of our government—to look at these issue in an inquiring, investigative way.

In a master’s degree program at Concordia University, which I entered after retiring from teaching, I began to understand that breast cancer and other issues could be depicted through art.

By creating works of art addressing what was going on at the time in the breast cancer community, I was able to bring the issues plaguing women to the attention of the public.

I was able to show how a personal experience could become a conduit for creative art-making.

My experience as an educator also came into play. By placing my work in the public arena, it became an instrument of viewer education. Awareness is the first step in understanding. It took 10 years of distancing myself from my breast cancer diagnosis before images relating to breast cancer again began appearing in one of my pieces.

What followed was a body of work representing the years I had spent as a BCAM board member learning how to be an activist."

How the body of work came to be

In Waterloo, 1999:

In a print making class I noticed my work had taken an unexpected turn. A collagraph image of a bra soon had a scalpel protruding from it.

And soon after, in a life drawing class, I had rendered the model tenaciously holding her breast and on the ground were severed breasts.

At this time the radical mastectomy was still being used; although it slowly began to disappear in the late 1980s, the lumpectomy was still new and was a suspicious procedure.

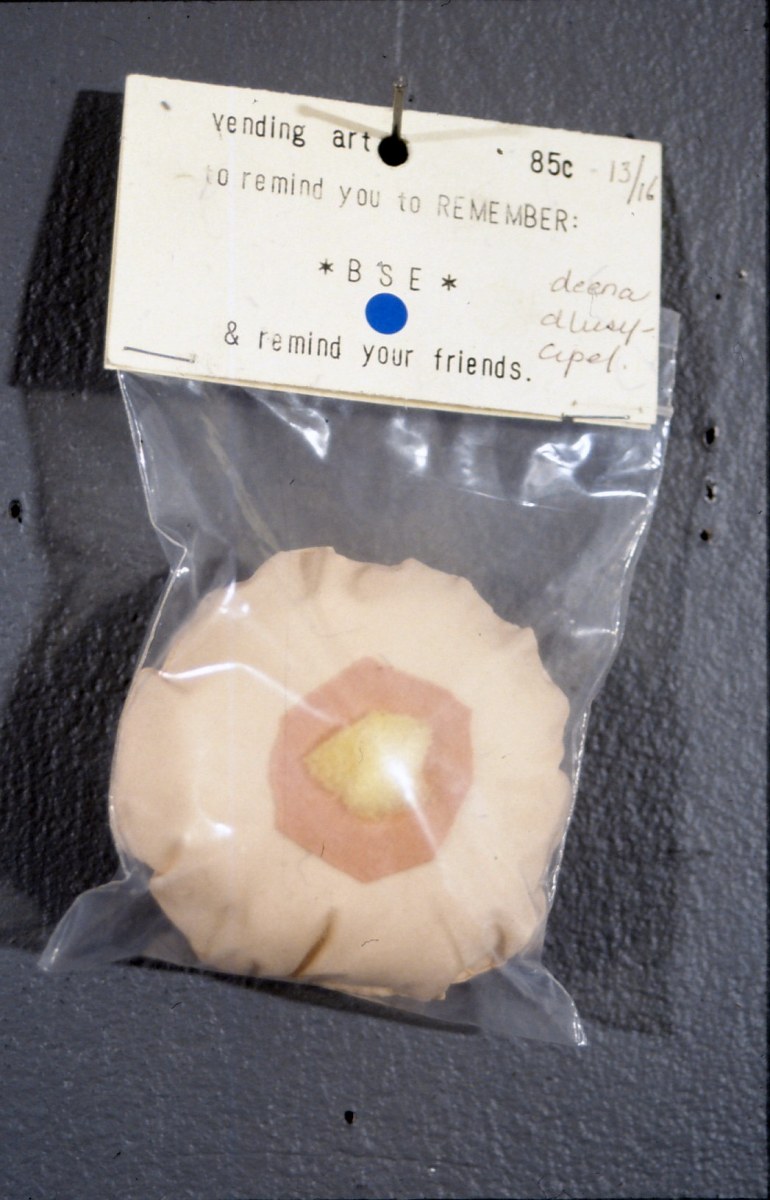

When my turn arose to contribute art to a vending machine which had different objects for sale on a weekly basis, I created a small breast made out of fabric. I labeled it “one in nine,” which represented the number of women in the population who would develop the disease. One out of every nine contained a mint the size of a breast lump.

The breasts were fabricated in all shades of human skin and were packaged with the following caveat: “This is to remind you to do breast self-examination and to remind a friend.” This body of work led to my thesis show at Concordia. I used text to explain where the work had come from and what I hoped it would do for others. The entire thesis can be found here; click the PDF button for “A personal portrayal of breast cancer: how art can educate.”

A more recent piece is one modeled after a BCAM picket sign that was used at a march held on Saint Catherine Street in Montreal. The message that day centered on the toxins in our environment and how we would like to eliminate them.

I also recommend a recent article in The Montreal Gazette where Cheryl Braganza, president of the Women’s Art Society of Montreal (WASM), writes about herself as an activist/artist. I am a member of WASM and have had the pleasure of meeting and speaking to Cheryl on many occasions. She recently showed a movie on her art and activism to the membership and delighted all with her presentation. The Gazette article is well worth the read: click here.